The 2010 Whitney Biennial opens tonight. Wish I was there. Congratulations Curtis Mann! The magazine Photography Quarterly (PQ), Issue #99 includes an interview with Mann. Check it out.

February 25th, 2010

The 2010 Whitney Biennial opens tonight. Wish I was there. Congratulations Curtis Mann! The magazine Photography Quarterly (PQ), Issue #99 includes an interview with Mann. Check it out.

February 24th, 2010

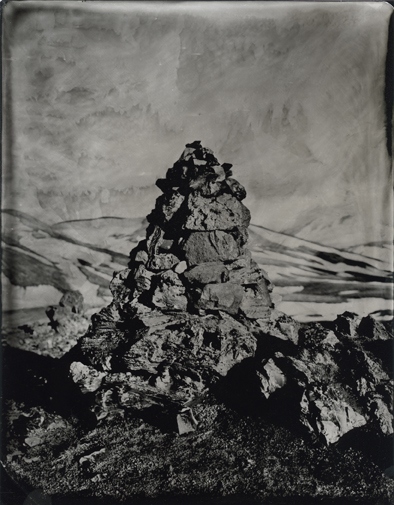

Arizona-based photographer, Christopher Colville is an up-and-coming star. Colville is redefining landscape photography and pushes the boundaries of the medium by embracing traditional and experimental processes. Through his imagery he explores the cycle of life, the passage of time, history, and our relationship to the landscape. Back in November 2009, I interviewed Chris right before his show opened at FotoWeekDC. The exhibition included work from three of Colville’s series – “Emanations,” “Iceland Trilogy” and “Sonoran Project.” Since the exhibition Chris has received the New Photographers Grant from the Humble Arts Foundation and was recently selected for Graphic Intersections v. 02 by The Exposure Project. And today, work from the series “Instar” is the featured photo on Flak Photo.

As mentioned in photographer Elizabeth Fleming’s blog, I have known Chris for a long time. He is a talented photographer flying under the radar. I’m glad his work is getting out there.

(This intro and interview were originally published in ArtVoices Magazine, December 2009.)

In his first solo show in Washington, D.C., Christopher Colville, photographer and teacher at Arizona State University, explores the themes of time as manifested in death and memory in a selection of work from his series “Emanations,” “Iceland Trilogy” and “Sonoran Project.”

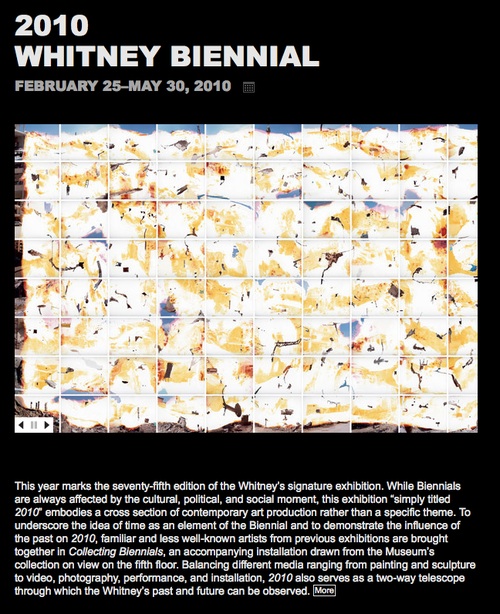

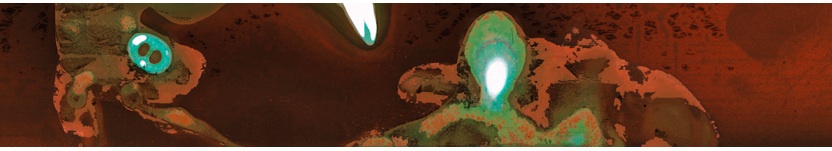

Emanation #1, Edition of 7, 42.5"x9.5" © Christopher Colville

Colville pushes the boundaries of the medium, embracing traditional and experimental processes. Included in his contemporary photographic work are photograms, ambrotypes, and decay-generated images. In “Emanations,” it is the energy given off from a decaying squid that exposes the photographic paper. Colville records this journey of life, of self, of death, in a myriad of colors that conjures up cosmic matter, unknown worlds, micro and macro ecosystems. It is ephemeral and magical.

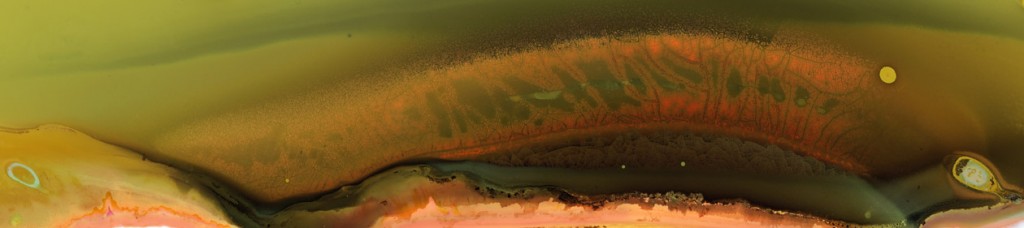

7/19/06, unfixed P.O.P photogram, 7"x5.6" ©Christopher Colville from Small Tragedies

“Iceland Trilogy” is an interconnected body of work of ritual and connection to the landscape. Two series within “Iceland Trilogy,” Cairns and Small Tragedies, are intimately tied together in terms of the artist’s ritual of creating one photograph each day in the Icelandic landscape of his ancestors. Cairns themselves are stones used to mark pathways, as well as markers placed as memorials to the dead. Colville reflects on his own intersection with the path of others – now and of the past.

7/23/06, Wet-Plate Ambrotype, 7"x5.6" ©Christopher Colville from Cairns

“Sonoran Project” is one of Colville’s latest body of work. Life in the Arizona desert is both miraculous and tenuous. In the vast landscape there are traces of life in all stages. His photograms capture a mythical spirituality of the natural world.

Bat, 2009, Edition of 12, 18.4" x 23", P.O.P. photogram ©Christopher Colville from the Sonoran Project

This selection of work seen together for FotoWeek DC, explores the cycle of life, the passage of time, history, and the landscape that embodies us all. The exhibition “Christopher Colville” is on view November 4 – December 11, 2009.

Larissa Leclair: Your process behind the “Emanations” series is absolutely amazing. This is an older series of work, but I am always drawn back to it. Who or what was your inspiration for that?

Christopher Colville: I wanted to make images that hinted at our connection to a more organic reality and the transformative nature of life. At the time I was thinking about how to do that photographically I was reading “The Beauty of the Husband” by Ann Carson and was struck by the passage, “[a] wound gives off its own light surgeons say. If all the lamps in the house were turned out you could dress this wound by what shines from it.” Carson’s quote brought to life a beautiful image of the power of healing and the suggestion that through pain we grow stronger and more full. That same week I learned from a friend that squid glow as they decompose and I couldn’t let go of the vision of an organism giving off energy in death. I think we all want to feel connected to something greater than ourselves, whether that is a religious spiritual connection or just an organic redistribution of our bodies providing nutrients for life after we die.

©Christopher Colville from Emanations

LL: I see that mythical spirituality of the natural world in all your series. Do you have any other contemporary influences?

CC: I have been thinking a lot about the work of Fredrick Sommer, Richard Long, Gabriel Orozco. Most recently I found the work of Cai Guo-Qiang extremely inspiring. I have also recently been influenced by the writing of David James Duncan and Cormac McCarthy.

LL: In William Jenkins’ essay in “Michael Lundgren: Transfigurations” (Radius Books, 2008) he begins, “[n]ot long ago Mike Lundgren, two others and I were camping in one of the most beautiful Sonoran desert landscapes I have ever encountered.” I know you have been camping many times with Mike Lundgren. Might Bill Jenkins be referring to you as well in this sentence?

CC: Probably not, but as it happens I am heading into the desert with Bill Jenkins, Mark Klett and many other ASU photo faculty and graduate students this weekend. Last week I spent four days in the Pinacate with Mike Lundgren and Richard Lagharn. We have a great community of artists living in the Phoenix area, many of whom seek refuge or solitude in the Sonoran Desert. One of the best things about living in Phoenix is the ability to leave the city quickly. For those people that are tuned in, the desert’s calling is hard to resist and sometimes it calls us out in packs.

©Christopher Colville from the Sonoran Project

LL: One of your latest series is the “Sonoran Project.” Can you describe the terrain of the Sonoran desert and how it is to photograph there?

CC: I don’t know if I will ever fully be able to describe the Sonoran desert and that is part of the reason I am compelled to spend time there and make work there. The terrain varies so greatly from seemingly barren flats to lush riparian areas as well as unforgiving mountain ranges. In the summer you hide from the sun by day and work through the night and in the winter the days are luminous and the nights are frigid. The terrain challenges you but at the same time I feel more at peace out there than anywhere else. In addition, the rich cultural history embedded in the landscape reveals itself in a way that resonates with my desires in art-making and enable me to feel connected to this greater history.

LL: Creating each one of your bodies of work seems to incorporate a prolonged period of time in the environment that you are photographing in–a journey if you will–and an exploration of self both physically and mentally. Do you agree?

CC: Yes. I am not interested in just documenting space. Instead my desires are more internal. They lay in an arena of sharing experience through the transformative process of image making. Life in the desert is both miraculous and tenuous. The harsh reality of the desert and the complex transitions speak to the evolution of life. The shifts in extremes–in the Sonoran Desert, in Iceland, and in life–resonate with the extremes of human emotion. In these spaces there is no insulation, yet life erupts from the most unexpected places. Spending time in the desert brings me closer to an experience that can escape the confines of language. It is an experience that is more essential, more tied to the immediacy of life. I feel that these more essential experiences reveal a lot about an individual. My work has always been about learning who I am–an internal dialogue that resonates on a broader level. How do we connect to this world? There is always a journey.

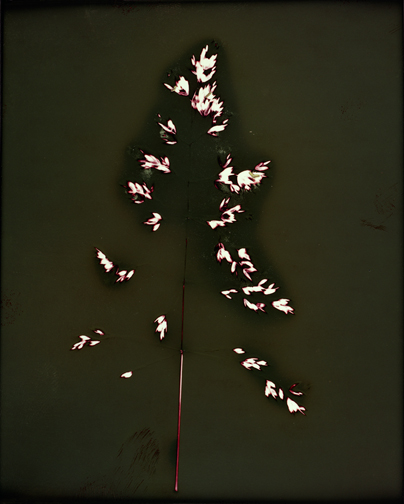

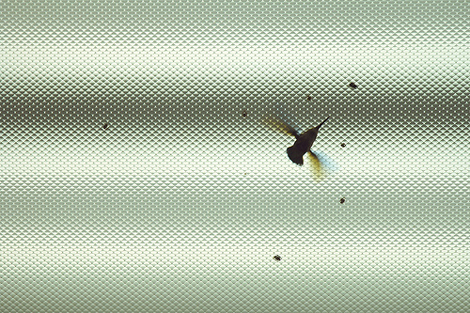

©Christopher Colville from Instar

Colville’s series Instar is also from the Sonoran Desert. About this work he says:

“Instar” describes the periods between successive molts of a caterpillar as it sheds its exoskeleton before reaching sexual maturity. Each molt leaves marks and scars on the body of the organism as evidence of its previous existence, similar to the marks left on the earth from natural events as well as the scars left on the landscape as we manipulate it for our needs.

I am interested in making images that translate the wonder and horror embedded in our landscape by these manipulations. The images in this portfolio represent one sequence from a growing body of work that uses the transformative power of photography to speak to our fears of life, death, and regeneration. These images reveal visions both apocalyptic and miraculous while searching for the possibility of redemption and beauty.

©Christopher Colville from Instar

To see more of Christopher Colville’s work, visit his website.

February 23rd, 2010

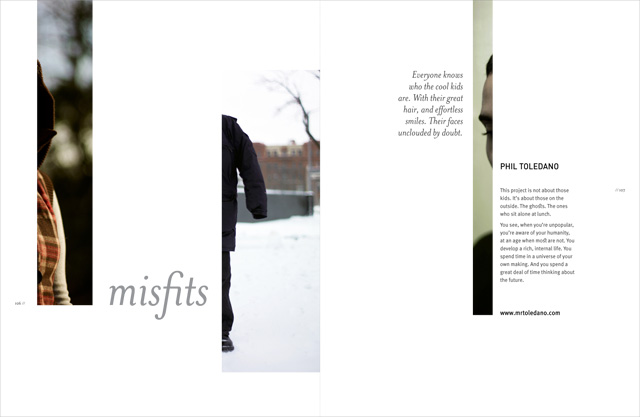

Love this magazine.

Love the selection of photographers, love the design, love the typography.

Unless You Will is an online pdf photography magazine out of Australia put together by photographer and designer Heidi Romano.

February 22nd, 2010

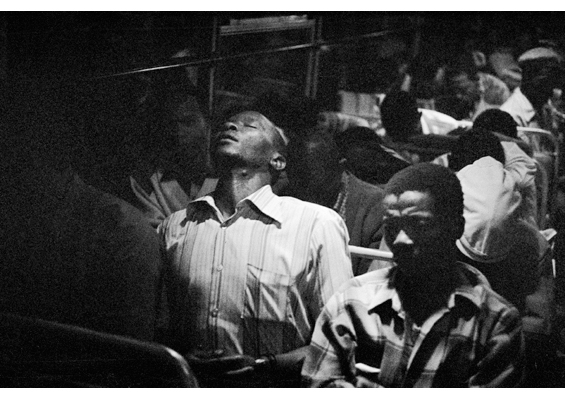

©Joao Silva for the New York Times

The front page of the New York Times today featured the story “A Bus System Reopens Rifts in South Africa” written by Celia W. Dugger with photographs by Joao Silva. It made me think of David Goldblatt’s black and white photographs from the 1980′s of the bus routes between KwaNdebele and Pretoria. I revisited Goldblatt’s work in the book The Transported of KwaNdebele published by Aperture and the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. Powerful work and a great compliment for Joao Silva’s more recent color photographs.

©David Goldblatt

February 17th, 2010

©Robert Adams

In the Darkroom: Photographic Processes Before the Digital Age

Co-curated by Sarah Kennel and Diane Waggoner

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

October 25, 2009 – March 14, 2010

Podcast interview with curator Sarah Kennel.

This is a must-see show. I have to admit that I spent most of my time reading the wall labels and text, but learned more from this exhibition than any history of photography class I ever took. It wasn’t until the second view of the exhibition that I was able to also focus on the subject matter of the photographs rather than just comparing and contrasting technique and process.

This is the way to learn about photographic processes. Co-curators Sarah Kennel and Diane Waggoner have concisely organized a chronological look at the different photographic techniques employed throughout the history of photography up until the digital age. Drawing from the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Art the exhibition includes examples of photogenic drawings, tintypes, daguerrotypes, ambrotypes, collodion negatives, paper negatives, waxed paper negatives, gum dichromate over platinum prints, gum dichromate prints, palladium prints, bromoil transfer prints, platinum prints, carbon prints, salted paper prints, albumen prints, books that compare photogravure reproductions and offset lithography for printing photography books, Polaroids, dye transfer prints, and chromogenic color prints from some of the most well-known practitioners of the medium. I haven’t even named all the processes included in the exhibition. Can anyone explain a Woodburytype?

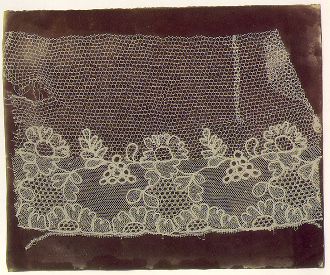

©William Henry Fox Talbot

There are many gems in the exhibition. On view are two delicate and beautiful pieces by Henry Fox Talbot; “Lace,” a photogenic drawing, and “Oak Tree,” a salted paper print. There are four photographs of Alfred Stieglitz’s “The Terminal,” printed as a carbon print, two silver gelatin prints, and a photogravure, that reveal his photographic thoughts in playing with composition (through cropping the printed image) and in utilizing different printing processes.

The Terminal ©Alfred Stieglitz

I loved the gelatin silver print of “Summer Nights # 2” (see first photo of this post) by Robert Adams and Edward Steichen’s “Cover Design,” as a duotone. Ansel Adams is featured with two prints of “Monolith, The Face of Half Dome;” one printed in 1927 that is soft and delicate in tone, and the other printed in 1980 that is larger in size, of high contrast, and very dramatic, the printing style most associated with Ansel Adams. Richard Misrach’s “Dead Fish, Salton Sea, California” is included as an example of a chromogenic color print, also know as a traditional c-print, as well as Saul Leiter’s “Snow.” And homage is paid to the Polaroid, with a few examples of this no-longer produced film, such as a manipulated SX-70, and a 20”x24” Polaroid transfer.

Snow ©Saul Leiter

I am already re-viewing the exhibition a third time, through the accompanying must-have catalog In the Darkroom: An Illustrated Guide to Photographic Processes before the Digital Age. It is an extremely useful reference for the breakdown and explanation of each photographic process.

UPDATE: There will be a free lecture with Sarah Kennel on Sunday, March 14 at 2pm at the National Gallery of Art, East Building Concourse Auditorium. A book signing will follow.

February 5th, 2010

Take one great photographer, Lisa M. Robinson, and one great social network, Andy Adams’ Flak Photo, (plus retweets by @flakphoto, @KLOMPCHING, @IsaLeshko, @FractionMag, @revoldrib, and @RossRawlings) and what do you get? A global audience. Soon after Lisa’s interview went live, Revol Drib of Thinking on Photography contacted me to translate it into Chinese for both his blog and for Chinese Photography Magazine, the leading photography magazine in China. To quote Lisa M. Robinson about the news; “How cool is THAT?!!” Read the original Lisa M. Robinson interview here.

(Please contact me if I missed your retweet.)

February 2nd, 2010

Hummingbird, from "100 Ways..." ©Kate MacDonnell

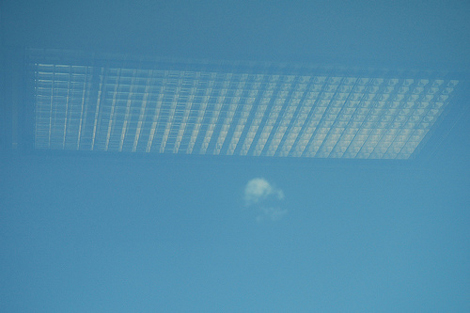

Kate MacDonnell is inspired by literature, poetry, music, and family in her often diaristic photographic work. “100 ways to kneel and kiss the ground,” the title of her ongoing series, is borrowed from a poem by the 13th century Persian poet, Rumi. MacDonnell finds wonder in the everyday. She meditates on the moments that make the common not so common–a hummingbird against the backdrop of a fluorescent office light; blue sky with a parhelion phenomenon. Her photographs rarely include people, but she sees the arrangement of personal space as a portrait of a person. MacDonnell highlights the particular while at the same time referencing the commonality in the individual and in doing so speaks to a larger shared existence.

Fire Rainbow and Flare, from "100 Ways..." ©Kate MacDonnell

Larissa Leclair: How did you get into photography?

Kate MacDonnell: I started in Painting and Drawing at the Corcoran. In my third year, I was frustrated with painting. I had the impulse to paint and to record little moments that I saw in the world, but wasn’t really attached to any subject. It was the act of looking that I was interested in doing. I spent a lot of time in the library and gathered books to take back to my studio to have a lot of visual resources to work with. I was doing paintings from death portraits and from other photographs. I came across William Eggleston’s Guide and was like, “Oh, I could take pictures!” In high school I had done black-and-white photography and my teacher had graduated from the Corcoran and was able to convince the photo department that I didn’t need to take the black-and-white classes and that I just needed to get into a color class. I ended up staying in the Fine Art Department, the Photography Department was separate, and just did color photography before there was much crossover between the two departments. I got to maintain my studio space that I had as a painter and hang all my color prints that I was working on. It was a beautiful situation.

Zach's Menorah, from "100 Ways..." ©Kate MacDonnell

LL: Are you still shooting color film and printing traditional c-prints?

KM: No, I do all digital now, but I consider going back.

LL: Did you begin your series “100 ways to kneel and kiss the ground” at the Corcoran? Tell me about that body of work.

KM: “100 ways” is post-Corcoran. I see myself doing a marathon–one thing morphs into another. I don’t know when it started. It is all digital and I started doing digital work in 2004. So I guess that would be a rough start date. David Lynch uses transcendental meditation as a source for creativity. He uses meditation every day and gets to a subconscious plane that we are all on and then uses that to create something. What I am doing is not that. I am thinking about that in a different way entirely. I am looking at the world for those things, those bits of visual evidence of ideas–that are relatable on a deeper subconscious level–and gathering bits of that. The creative part is in the editing–putting these disparate little moments together that hopefully resonate with anyone viewing the images.

Weston, Campion Center, from "100 Ways..." ©Kate MacDonnell

LL: Your work is very meditative and poetic and I do see those little moments–personal spaces, personal arrangements, and personal things–which speak to a universal commonness. Let’s talk about the titles of your photographs–they are very specific. There is a lot more that you can read into the image when you take into account the title.

KM: I didn’t title my images for a long time. That was the idea: the communication is the image itself, to have that direct relationship with the image without being told some other little piece of information. I liked the directness of it. But then titling work, especially when things are more abstract, acknowledges your connection with the image that you’ve made, and it can help convey the image to the viewer in that they see there is some sincerity to it, some other way in. Language is another way to help it be more accessible. I want the images to be accessible. I don’t want to shut the viewer off.

Sky Cartography for Common's Father, from "100 Ways..." ©Kate MacDonnell

LL: Can you explain the title “Sky Cartography for Common’s Father?“

KM: Do you know the rapper Common Sense? His father is a poet, Lonnie Lynn. He is always on Common’s records doing spoken work. Poetry and literature are very important to my work. It could be Milan Kundera; it could be Rumi; it could be Lonnie Lynn. I’m interested in the human thread. So the album is “Be.” Lonnie Lynn does a spoken word piece on the last track and he can’t say the word cartography. He says, “Be a car … topographer,” and then laughs a bit, “Be a maker of maps … ” He owns the way he just goes right over it. It’s awesome. He also says, “Be the author of your own horoscope.” I like that too. The image reminded me of a crude map of the U.S. and I thought about this poem and the kids that are all saying what they want to be at the beginning of it. And I thought that I would want to be a maker of maps, but of the sky.

LL: I also see a spiritual and metaphysical dimension to your work. Is that a conscious decision?

KM: [It is] as conscious as the spiritual or metaphysical is in my life, in my interaction with the world.

LL: Which it is.

KM: Yeah definitely. That’s there.

The Fountainhead, Ocean City, MD, from "100 Ways..." ©Kate MacDonnell

LL: Are there 100 images in “100 ways to kneel and kiss the ground?”

KM: No, and on purpose, 100 is not what Rumi meant. What Rumi means is there are infinite ways. The body of work has an infinite number of images that can be added to it in the future, or images that I already made, in a “negative notebook” somewhere that might be part of it but that I just don’t have in the series yet.

LL: You are represented by Civilian Art Projects (DC). How did you come to work with Jayme McLellan? And what role does working with such an influential curator have on you as an artist?

KM: Jayme is amazing. She is like a force of nature. I have great respect for what she is doing and has done for the DC art scene. She gets work that might not be as commercially viable in this town out there and on view to challenge us in DC as viewers. I met her when I was in a group show that Colby Caldwell curated at DCAC back in 2001. She was working there at the time. Fastforward several years to when Jayme had gotten a (semi) permanent space in DC for Civilian Art Projects which, in the first several months of its existence had been utilizing alternative spaces, collaborating with other galleries, etc in order for Jayme to show work that she cared about and wanted to get on view. Jayme invited me to be represented sometime in late 2007 after the gallery had landed at the 7th and D location. And I had my first solo show at Civilian Art Projects in spring of 2008. Jayme is great to work with because it doesn’t feel like work. She allows for me to have my own autonomy, but has an understanding of my work and a photographer’s eye and an analytical yet idiosyncratic mind. I trust her editing and sequencing and was really pleased with the 17 images that she curated into the show from the 100+ that she had seen. The ideas and major themes of the body of work were accentuated through her edit. What makes her such a joy to work with is that she allows for true collaboration. For example when our opinions on the layout of the show differed, Jayme listened to my rationale and accommodated my concerns while keeping her vision for the show clear and concise. I was really pleased with the show.

Joe's Grave, from "100 Ways..." ©Kate MacDonnell

LL: Your work would do well in book format.

KM: I have done a couple of self-published books. There are a million companies out there. I have done Blurb, Snapfish, Lulu, ibook. I’ve done a bunch. They are functional, a great way to work out editing and sequencing. To me they are a taste but not very satisfying. The not satisfying part is the print quality. For instance, for the 100 ways show, I worked with Soung Wiser of DC’s General Design Company and Jayme to create a book that would go along with the show. Jayme, Soung and I all worked together to edit and sequence the images. Soung worked on the layout within the confines of the Blurb software at the time. Now both the layout options  and the paper quality have improved, but at the time the quality of the paper and printing didn’t warrant the price of production. But, yeah, I love photo books as a medium. It is such a nice intimate way to view a collection of images. I would love to have a nicely published short-run trade edition eventually.

and the paper quality have improved, but at the time the quality of the paper and printing didn’t warrant the price of production. But, yeah, I love photo books as a medium. It is such a nice intimate way to view a collection of images. I would love to have a nicely published short-run trade edition eventually.

LL: As an artist, why choose Washington, D.C.?

KM: It’s home. I’ve never lived anywhere else. I grew up right outside of D.C. and came to school in D.C. and then just stayed here. We have this idea or ideal in the U.S. that you should move around and I’ve kind of had the impulse now and then but I also like the idea to be close to where I am from. I have family in the area. I like having deep roots.

Blank, from "100 Ways..." ©Kate MacDonnell

LL: Do you photograph every day?

KM: Yeah, pretty much. I carry the camera with me, street photographer style.

LL: How was it photographing every day for “SAMETIME 7:15”?

KM: That was really awesome. It was a fun project to work on. As much of a pain as it was to have to commit every Sunday night to uploading and captioning the images, it was always fun to see on Monday what had come together from everyone. As a photographer doing a solitary pursuit, it is nice to have that feeling of connection with other people in the community on a daily basis. It is rare that that’s the situation, and daily for a year. That connection is really bolstering to the creative process. Michael Lease, one of the artists that started the SAMETIME project, insists on community.

Reflection and Cloud, from "100 Ways..." ©Kate MacDonnell

LL: When you write about your own work you mention the new topographics movement, which coincidentally the original exhibition has been restaged at LACMA [Los Angeles County Museum of Art]. How are those photographers–Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, etc.–influential to you?

KM: They were part of my impetus to do photography. I was born in 1975 when that show happened. I was born into the world that they were making images of. I was born into one of those cookie-cutter houses, in a cookie-cutter community. Here they are from the outside saying, “This is house, house, house, house.” They were speaking to these places being devoid of aesthetic value because they were these manufactured environments–man’s imposition on the landscape. But I am like, “Well, no, because I live inside it, and this house faces this way and that one faces the woods. It is the same box but it faces the woods. Their stairs face that way and on their stairs they have a fake tree.” There are lives being lived here. Growing up in that environment was a bit surreal but the similarity was comforting. It was like a David Lynch type normalcy. Every house is the same, but the stuff in it is different and its orientation to the street shifts. It is interesting to see how people treat the same thing differently and make it their own. I’m interested in these little intricate details. Along with wanting to make images that denote the humanity of these places, I was keenly drawn to their seemingly simplistic but in fact, very subtle and sometimes sublime use of composition. I like the feeling of looking at images that are like still waters.

Leaves Fall, from "100 Ways..." ©Kate MacDonnell

LL: You are still continuing on with “100 Ways”. Are you working on any other series?

KM: The 100 ways work is morphing into something more ethereal. They’ll need more space. I’ll be printing them larger. The working title is either “Elements” or “What We Got.” And I have started to photograph on Florida Avenue in DC, the hand-painted address signage. That is just starting to take shape. Florida used to be Boundary Street. That was it. That was DC. So, I am photographing the old edge of the city -like in European towns that have the concentric walls of the expanding outer edge of the city. I like the layering that happens over the course of time as well as recording a moment in the history of the evolution of the city. This collection of intimate indicators of place are in that same vein of celebrating DC’s unique look as Ken Ashton‘s DC Theaters and his DC neighborhoods projects as well as Lely Constantinople‘s Georgia Avenue project. So, the work will be in good company.

Fireworks ©Kate MacDonnell

Looking for Constellations ©Kate MacDonnell

Snow ©Kate MacDonnell

Painted over peep street art ©Kate MacDonnell

600 T Street ©Kate MacDonnell

LL: Thank you Kate.

Kate MacDonnell is represented by Civilian Art Projects (DC). Read an interview (2008) with director Jayme McLellan.

MacDonnell’s Blurb book can be viewed here.

MacDonnell’s work is part of “Empty Time” curated by Trevor Young at the Fridge (DC). Opening February 6, 8-11PM.

This interview was also published in a shorter form in ArtVoices Magazine, January 2010.